Point Centers, a New Breed in the NBA

By Mark Cheung | October 30, 2019

Since the invention of the three-point line in 1979, five positions have been established in the NBA: point guard, shooting guard, small forward, power forward, and the center. While the NBA rule book never explicitly acknowledges these positions, they still seem so inherent to the game of basketball. It’s nearly impossible to imagine the game without them because, for decades, almost every basketball coach, player, and fan has believed that this how basketball should be played.

However, today’s NBA has gradually deviated from these traditional positions as teams have attempted to discover new competitive advantages. This phenomenon has been dubbed as “positionless basketball” by many basketball analysts, coaches, and players alike. In 2017, Brad Stevens, head coach of the Boston Celtics, explained how this paradigm shift has affected his coaching, “I don’t have five positions anymore. It may be as simple as three positions now, where you’re either a ball-handler, a wing, or a big”. What this looks like in actual games is that teams are no longer playing players at certain positions strictly based on archetypal attributes. For example, in the Warriors’ historic 73-9 season, their 3rd most frequently-used five-man lineup consisted of no players taller than 6’8. And that lineup, featuring Steph Curry, Klay Thompson, Harrison Barnes, Andre Iguodala, and Draymond Green, proved to be the Warriors’ most successful 5-man lineup that season - outscoring opponents by an average of 45.1 points per 100 possessions.

While positionless basketball has affected the usages and roles of every position, centers have felt the repercussions the most. More and more tall players have been adopting skill sets traditionally employed by guards. As a result, many players of a conventional center’s height aren’t considered centers in today’s NBA. And many of those who are considered centers in today’s NBA play much differently than the centers of previous decades. In Philadelphia, six-foot-ten Ben Simmons runs the point rather than exclusively playing in the paint. In Milwaukee, six-foot-eleven Giannis Antetokounmpo receives playing-time at every position, despite being the height of an average center. And in Denver, Nikola Jokic, standing at 7’0 and 250 pounds, consistently leads his team in assists, despite playing center. With Ben Simmons, Nikola Jokic, and reigning-MVP Giannis Antetotounmpo being three of the brightest stars in the NBA, it’s clear that the concept of the traditional center is fading.

Shooting has been the biggest factor of change amongst centers, but passing might be the most underlooked aspect. Centers across the NBA have become increasingly involved within their team’s offensive playmaking over the past five seasons. By having centers play a larger role in orchestrating the offense, guards and wings are provided with more flexibility and freedom off the ball. One way for teams to accomplish this is by having their center assume the role of the primary ball-handler in a play, especially from a post-up position. By posting-up, the center becomes an immediate scoring threat, thus drawing defensive attention away from his teammates.

With Saric’s defender focused on Towns’ post-up, Saric is able to unimpededly cut towards the basket. Towns then connects with Saric on a timely over-the-shoulder pass.

Another way teams have adopted this strategy is by having their center act as the primary ball-handler above the break rather than from in the post. By doing so, the opposing center is taken out of the paint - creating a 5-out or a 4-1 set. This generates a valuable opportunity for teammates to cut to the basket without having to worry about being contested by the opposing team’s center, who is often times the defense’s best rim-protector on the floor.

With center Nikola Jokic playmaking from the perimeter, there are zero players in the paint. This vacancy allows Craig to make a back-door cut and score an easy bucket off of Jokic’s assist.

Another similar strategy that teams have employed is utilizing their center like a point guard on fastbreaks. This allows quicker players to immediately run the break rather than waiting for an outlet pass by their center to initiate the break. This also forces the opposing team’s center to have to get back on defense promptly.

Right off the defensive rebound, Al Horford starts the fastbreak by himself. As a result, Morris and Tatum are both able to run in transition immediately and function as scorers on the break.

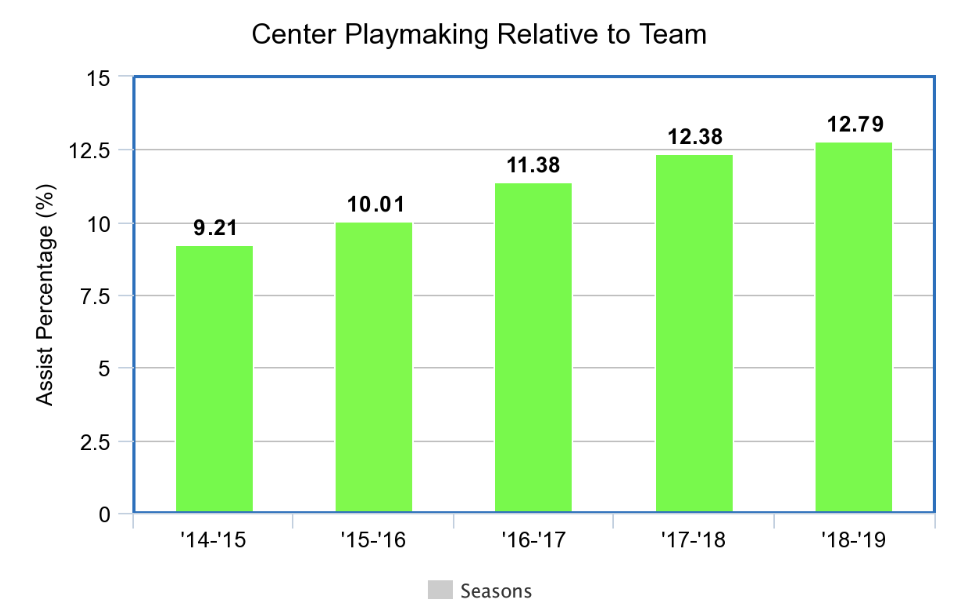

We can measure the effects of this newfound playmaking role for centers through assist percentages - which tells us the percentage of a team’s field goals a player assisted on while on the floor. The assist percentage metric is useful because it provides more context than a statistic like assists. While it would seem notable if centers were averaging more assists per game than in previous years, it would mean little if teams were simultaneously attempting and making more field goals than in previous years. An assist percentage accounts for this because it is relative to a team’s field goal attempts. The graphic below measures the average assist percentage by the 30 centers who received the most minutes per game in each season since 2014-’15.

Since 2014-15, the average assist percentage of centers has gone up 3.58%, indicating that centers are now creating a higher-proportion of shots for their teammates than in previous seasons. For reference, the median NBA team assists on 60.1% of their made field goals. With centers assisting on an average of 12.79% of their team’s made field goals last season, they are accounting for over one-fifth of the median NBA team’s total assists - despite being considered as one of the least-qualified positions to facilitate the ball.

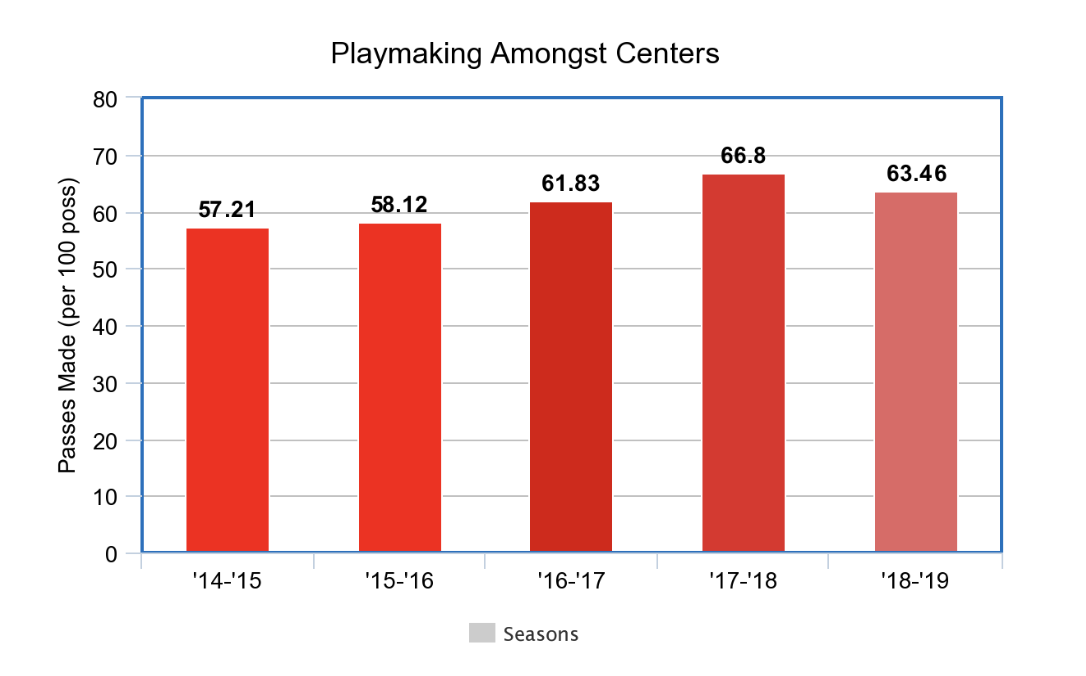

However, we can’t just quantify a player’s passing ability strictly off of assist percentage because a play unfolds much prior to the final scoring play. We can measure a center’s overall playmaking involvement by tracking the average amount of passes made by centers. By tracking passes made rather than assists, it allows us to gauge how often a center is being involved in the flow of the offense - even if they aren’t the one making the final pass on a play. Below is a graphic of the average passes made per 100 possessions by the 30 centers who received the most average minutes per game in each season since 2014-’15.

The average passes made by centers has increased every season since 2014-15, with the exception of a dip last season. In just the span of the first four seasons (‘14-’15 to ‘17-’18), the amount of average passes made by centers went up by 16.76%. And while that dip in the following season does upset the trend, that could be attributed to the injuries to Pau Gasol and Demarcus Cousins - who accounted for a combined 167.47 passes made per 100 possessions in 2017-18. This increase in passes made per 100 possessions goes against the notion that the offensive role of centers has been decreasing recently. Even though the NBA may be a guards’ league now, that doesn’t mean that the role of the center has diminished. Rather, it has transformed.

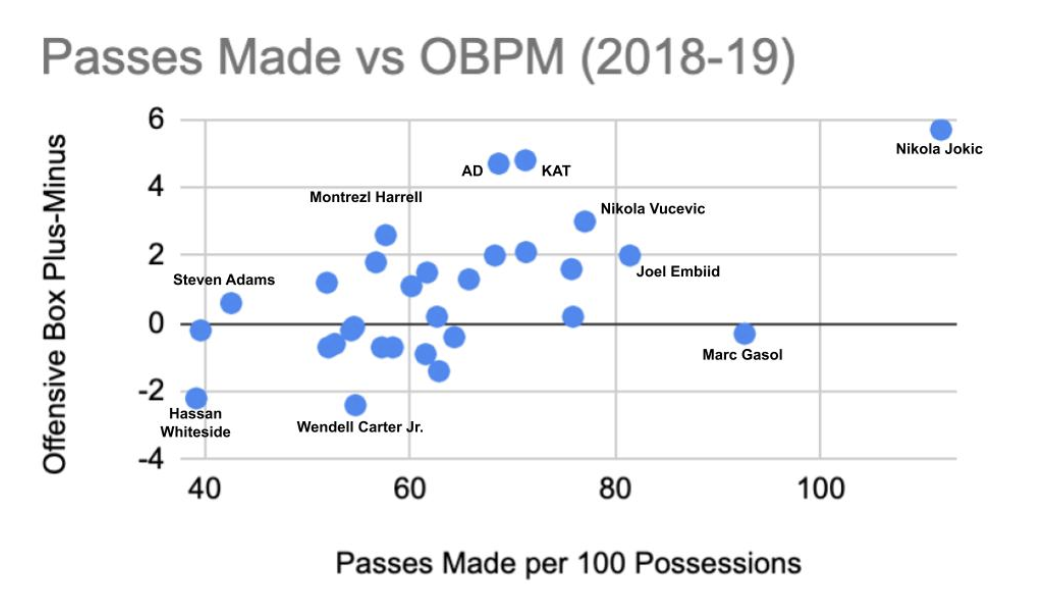

This increase of facilitation amongst centers isn’t without reason. Traditionally, centers were often utilized in offenses for two purposes: screening and scoring. By providing them a passing role, centers have opened up a greater variety of offensive options for their team. The positive trends in both passes made per 100 possessions and assist percentage imply that these offensive strategies are working - or else, centers would have resorted back to their traditional uses of screening and scoring. We can measure the association between center playmaking and offensive success by graphing offensive box plus-minus against passes made per 100 possessions and assist percentage.

Offensive Box Plus-Minus (OBPM) is a per-100 possession metric that uses a player’s offensive statistics relative to their team’s offensive performance to estimate that player’s offensive performance compared to a league-average offensive performance. A league-average offensive box plus-minus is 0.0. A negative OBPM suggests that a player has an offensive impact below league-average while a positive OBPM suggests that a player has an offensive impact above league-average.

In the graph between passes made per 100 possessions versus OBPM, there’s a noticeable positive, linear trend. Generally, centers with more passes made per 100 possessions had higher OBPMs. The graph has a correlation coefficient of r = 0.586, indicating a moderate linear relationship between passes made and OBPM (r = 1 would indicate a perfect linear relationship and r = 0 would indicate no correlation). It’s not a perfect relationship, but it’s still visible. Just by looking at the graph, it’s evident that all centers who averaged more than 70 passes made per 100 possessions also had a positive offensive box plus-minus except for Marc Gasol, who had a -0.3 OBPM.

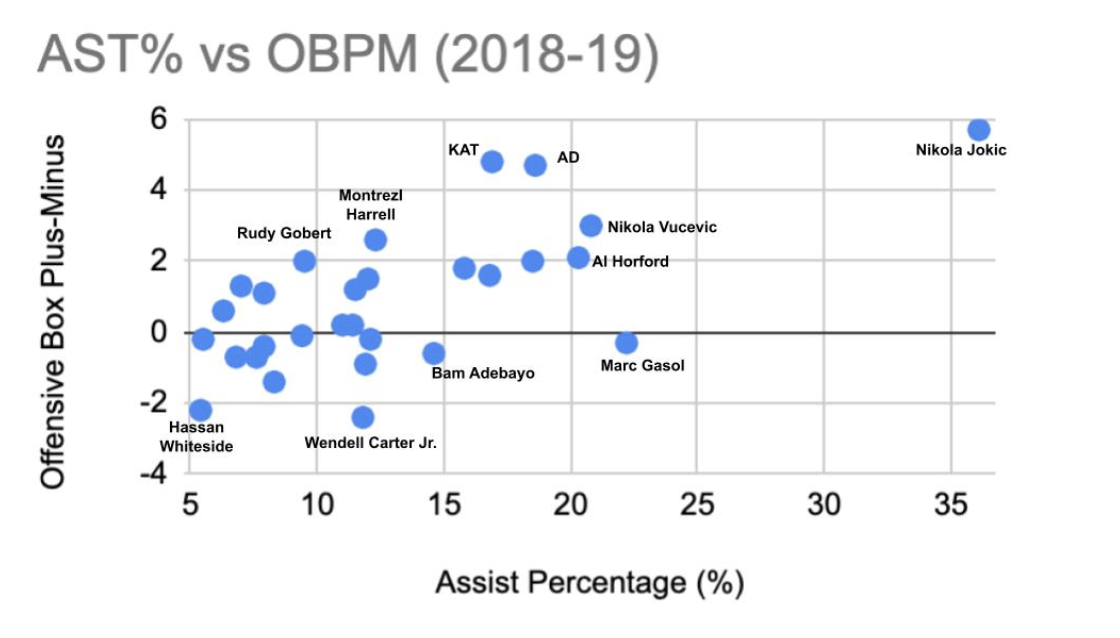

The graph between assist percentage and offensive box plus-minus exhibits a clearer positive, linear trend. It has a correlation coefficient of r = 0.676, indicating a nearly strong linear trend. From the graph, it’s apparent that all centers with a negative OBPM also had an assist percentage lower than 15%, except for Marc Gasol.

In both graphs, it’s not hard to notice that the most awarded and renowned centers also have the most passes made per 100 possessions, highest assist percentages, and highest OBPM. Nikola Jokic, who was crowned All-NBA First Team and finished 4th in MVP voting, is remarkably ahead of the pack in all three categories. Six-time All-Star Anthony Davis, two-time All-Star Joel Embiid, and two-time All-Star Karl-Anthony Towns are all ahead of the median in all three categories as well. Nikola Vucevic, who was a first-time All-Star last season, has quietly also found himself very high in all three categories.

This isn’t to say there is a direct correlation between passes made and OBPM, or assist percentage and OBPM. It makes sense that star offensive centers will have the opportunity to have more passes made per 100 possessions or higher assist percentages than other centers because they receive more touches per game. However, just by having more touches per game doesn’t automatically equate to solid playmaking skills. But I think a player like Nikola Jokic is a credible testament to the importance and value of passing amongst centers. Last season, Nikola Jokic’s involvement in the Nuggets’ offense was not much higher than Joel Embiid’s - if at all. In fact, an argument can be made that Embiid was a better scorer last season than Jokic. But Jokic’s impact and value to the Nuggets’ offense was much higher than Embiid’s in terms of OBPM because of Jokic’s ability to function as a playmaker. That goes to show that scoring ability amongst centers doesn’t always dictate who the better offensive player is. Jokic’s playmaking ability makes up for any gap in scoring abilities, and then adds additional value.

The NBA is a league of followers. If a strategy results into winning, every team will assimilate. After Daryl Morey’s revolutionary three-pointers analytics and the Warriors’ Splash Bros, the NBA experienced a complete offensive overhaul. Now with the tremendous success that Nikola Jokic has been experiencing, it’s very plausible that a new breed of centers is on the horizon - one that places more emphasis on playmaking. Either that, or the traditional center position transitions into a hybrid position - which takes both the height of a traditional center and the skillsets of a guard. In both cases, playmaking will become a more valued aspect of a bigman’s repertoire. Conversely, volume scoring may be less emphasized for centers in order to balance their offensive duties. After all, Wilt Chamberlain didn’t win his first championship until he cut his field goal attempts by nearly half and increased his assists by almost 50%.