Speed Kills?

By Maui Simon | November 1, 2019

In recent years, the National Football League has undergone several drastic changes. Fans continue to crave high-scoring, dramatic offensive battles and resist a return to the gritty defenses of the past. Accordingly, it seems that the NFL has adjusted its rules to favor offenses. Quarterbacks are being protected by flags more than ever before it seems, with many controversial late hit or targeting penalties significantly alter many crucial games. Meanwhile, it appears that cornerbacks and safeties are hardly even allowed to touch opposing wide receivers, whereas wide receivers, on the other hand, are frequently getting away with so-called “pick plays,” where they allegedly unintentionally run into opposing defensive backs. NFL teams are embracing these structural changes.

Adopting these structural changes into their philosophies, quarterbacks are now soaring to the top of draft boards, even without world-breaking talent. Mediocre quarterbacks are being grossly overpaid (I’m definitely not looking at you, Kirk Cousins) while many defensive positions are being significantly devalued. Additionally, offensive coordinators have incorporated these paradigm shifts by prioritizing speed over power and attempting far more passes than runs. Receivers and running backs are expected to be even faster, and not necessarily as physically imposing, while offensive linemen are required to be more athletic. Defenses have responded accordingly to match the speed of offenses, by acquiring faster defenders and using sub-packages with more “hybrid” defenders who are more fast than physical.

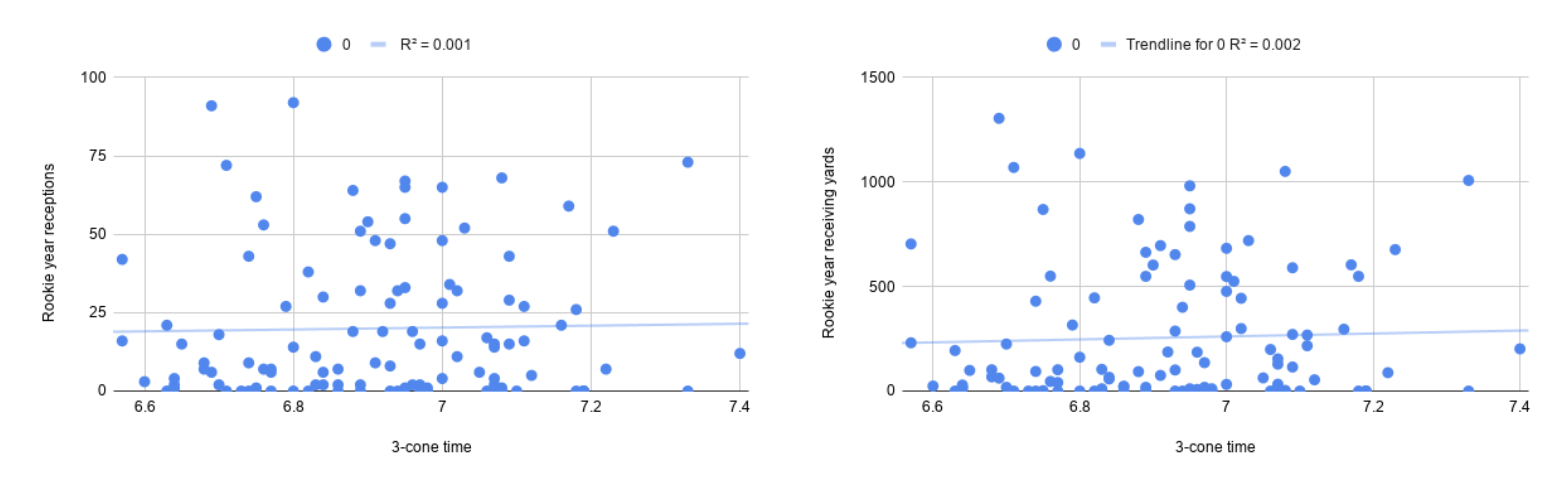

Combined with fans preexisting affinity for speed (we love to dream of being fast as Flash and watching insane sprinters like Usain Bolt), the continued evolution of the game has elevated speed metrics to the top of fans’ interest. For many true fans, their anticipation for the upcoming season can spiral until the point where they have nothing better to do than watch the NFL combine (I must admit I usually watch the NFL combine despite telling myself I won’t, and I usually still come away disappointed). Watching the combine, it seems that everyone is hyper-focused on one marquee event: the 40-yard dash, a measure of a prospect’s straight-line speed. This event is particularly noteworthy for skill positions like wide receivers, running backs, tight ends, and defensive backs. Just recently, John Ross III broke the combine’s fastest ever 40-yard dash time with a blazing time of 4.22 seconds, and receiving prospect Henry Ruggs III of Alabama is expected to approach that time in this upcoming combine. Yet, after watching John Ross sputter for most of his young career as a receiver, it is fair to wonder how well 40-yard dash times and raw speed correlate to NFL success. Instead, I would like to examine a different metric, one which many scouts consider to be a better indicator of a prospect’s potential as an NFL receiver: the 3-cone drill, used primarily to measure quickness, fluidity, and agility. Looking only at wide receiver prospects who actually ended up playing in the NFL, I will examine how a prospect’s 3-cone time correlates to their immediate NFL success. I will measure success as a wide receiver’s receptions and receiving yardage in their rookie seasons from the past 5 years. A receiver’s success in their rookie season is a critical metric, as successful rookie receivers often have successful careers.

The above analyses plotted over 100 rookie receivers receptions and yardage outputs vs their combine 3-cone time. For both scatter plots, the lines of best fit and extremely low R² values reveal that there is actually little correlation between a receiver’s 3-cone time and how well they perform in the NFL their rookie season. Even a cursory glance at some of today’s most notable receivers will highlight this result. For example, Odell Beckham Jr., one of the most explosive receivers in today’s NFL, ran a blazing 6.69 second 3-cone drill that would corroborate the intuition that a good 3-cone time translates to NFL success. Conversely, DK Metcalf ran a very subpar 7.38 second 3-cone time, but has already had a very successful rookie season to date. On the opposite end of the spectrum, many prospects have run very fast 3-cone times and completely floundered in the NFL. Naturally, this all implies that it is unlikely a single combine metric can accurately predict the success of a receiver. A receiver’s success in the NFL is likely a product of numerous measurable and intangible factors, not just their speed or quickness individually. It sure would be a lot easier for scouts, however, if 3-cone times did predict success!

Limitations:

A couple of confounding factors must be noted. For one, this analysis doesn’t take minor injuries into account (major injuries resulted in a player being removed from this analysis, such as Colt’s Deon Cain), but injuries are obviously a big, sometimes unavoidable part of the game. Second, wide receiver’s are of course expected to have diverse skill sets and different teams draft players for different reasons. For some teams, a wide receiver may be drafted because they have very admirable raw skills, including 3-cone time, but aren’t expected to play right away. They are considered development projects. For other prospects, they are technically wide receiver’s but perhaps expected to primarily play on special teams. At the same time, though, this is part of what I am seeking to uncover in this analysis: whether a prospect’s 3-cone time can enable them to transcend expectations and perform well at the next level. To reiterate, it has been found that while a good 3-cone time is of course a beneficial quality, it cannot accurately predict a receiver’s success.