Investing in Bigmen

By Mark Cheung | March 23, 2021

At this point, what even are bigmen? On some nights, the traditional concept of the stout and sturdy seven-foot paint presence burns bright. But on other nights, the 6’4” former-PG Bruce Brown is just as much of a bigman as Deandre Jordan.

It’s no secret that the bigman position has been branching out its roots over the past few years (this is something I explored in my inaugural piece for SAGB). Since that article, this trend has remained steadfast - bigmen have continued to expand their domain outside of conventional bigman roles. Additionally, as of the past year or so, we’ve also seen a seemingly significant uptick in the opposite trend as well - that more and more non-big players have been dabbling into bigman roles.

Because of the bigman position’s increasingly varied constituents - most of which are capable of polar swings in impact based on different matchups/fits/playstyles - I suppose you could think of different bigman archetypes as like stocks - and it’s up to front offices to predict which archetypes could boom/bust in their system.

Under this crude (and probably overused) stock market analogy, the draft is essentially when GMs make their “investments” in these “stocks”. Ideally, the goal for front offices is to draft an archetype that appreciates over the upcoming seasons. Worst-case scenario is that you spend an expensive asset on a prospect with a depreciating skillset - aka the infamous case of former 3rd overall pick Jahlil Okafor.

But, I get it. In real time, it’s hard to predict with 20/20 vision which archetypes are going to soar/tank in value in the future - especially for a position as volatile as bigmen. So let’s not aim for sleuthing the next big archetype sensation or extinction. Instead, perhaps we can attempt to get a solid idea of the overall direction in which the bigmen stock market is trending - simply by assessing the current state of the market in order to see which archetypes are returning the most value (impact) and which archetypes are being invested at the lowest/highest prices (draft selections). That way, we can evaluate the best/worst ways for NBA teams to draft in the present.

Setting up the Project

In order to discover potential inefficiencies in the way bigmen are being drafted, I decided to group every bigman (who tallied at least 400 minutes and 20 games played) from the 2019-20 NBA season into 5 distinct archetypes using k-means clustering so that we can assess which styles of bigmen are punching above/below their draft position (a method inspired by the great Todd Whitehead ). The basic idea is that k-means clustering finds a stratification of our bigmen in a way that minimizes the differences between player stats within each cluster - in other words, it puts our bigmen into clusters in which bigmen of the same cluster have similar stats. The list of stats used in this k-means clustering is quite lengthy, but the meat of it includes tracking stats, shot-location distribution, defensive versatility, and playtype frequencies.

Once every big has been placed into a cluster, the next step of the plan is to look at the average draft position of each cluster and compare that to the average impact of each cluster (I used FiveThirtyEight’s RAPTOR as the measurement for impact, which is a a plus-minus statistic that uses box score stats and on/off ratings to estimate a player’s point contribution to his team per 100 possessions). Ideally, if teams are drafting correctly, the clusters being drafted the highest on average should also have the highest impact on average.

The Project

By performing k-means clustering, it finds that these are the clusters that best separate our bigmen.

Cluster 1) All-Around Bigs

Cluster 2) Mobile, Handling Bigs

Cluster 3) Run-and-Jump Bigs

Cluster 4) Versatile Forwards

Cluster 5) Two-way Stretch Bigs

(Note: The clusters were named by me based on common denominator skills that I observed in each cluster. The labels had 0 effect on how the bigmen were put into clusters since the labels were given after the clusters were already constructed.)

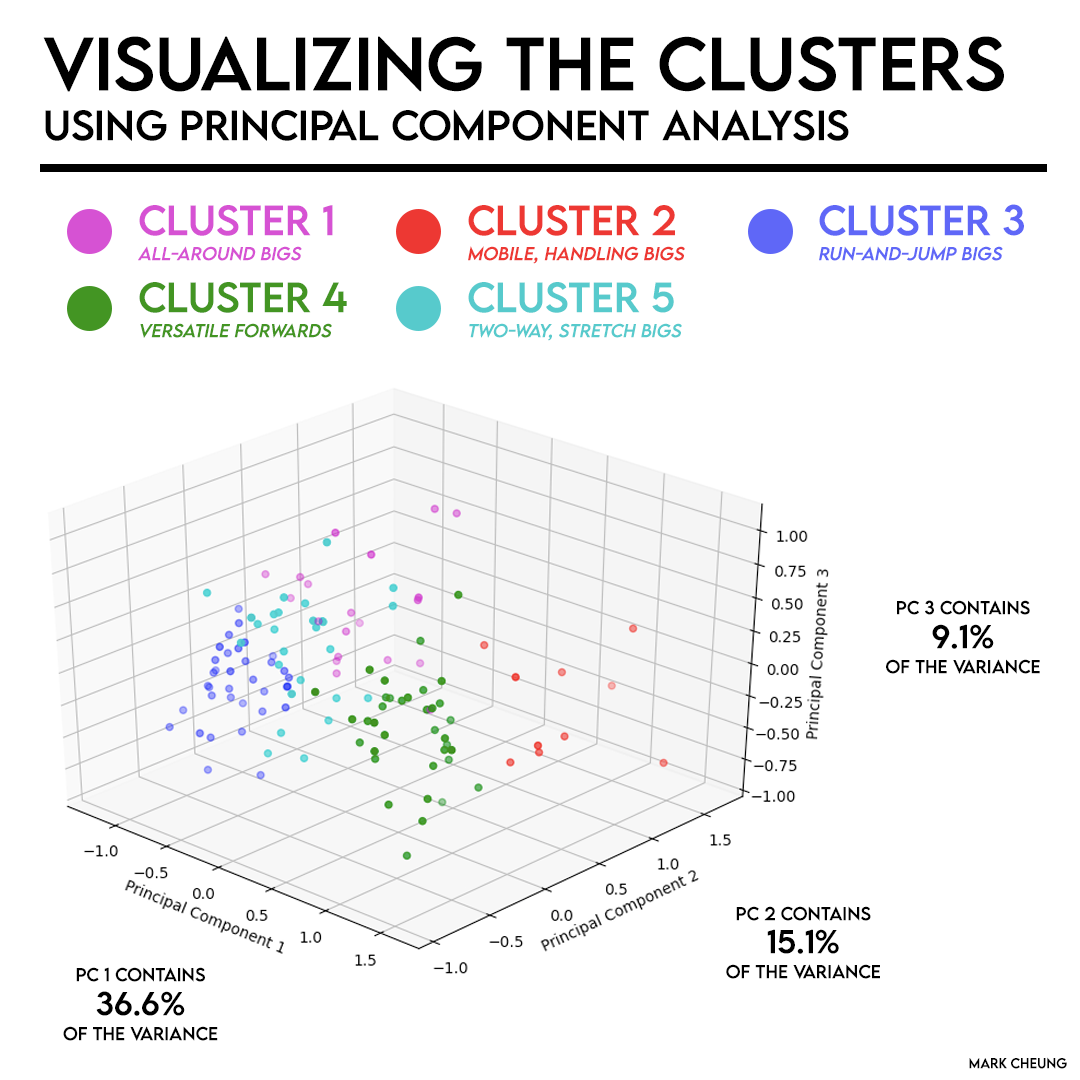

Here’s what these clusters look like graphically. Essentially, this plot places all our bigmen into this 3D space based on their stats, where each axis is a linear combination of the stats we used to cluster them (Note, some information is lost when downsizing to 3 dimensions).

Just by looking at the locations of each cluster, you can get a pretty good sense of which clusters are most/least related to each other.

For example, Run-and-Jump Bigs (the dark blue cluster) overlap slightly with Two-Way Stretch Bigs (the cyan cluster), perhaps because of rim-protection. Versatile Forwards (the green cluster) seem to be cousins with Two-Way Stretch Bigs, probably because of their shooting. Meanwhile, Mobile-Handling Bigs (the red cluster) are the most separated from the rest of the players, which makes sense when you consider that unique talent like Giannis, AD, Siakam, and Draymond populate this cluster.

Translating to Basketball

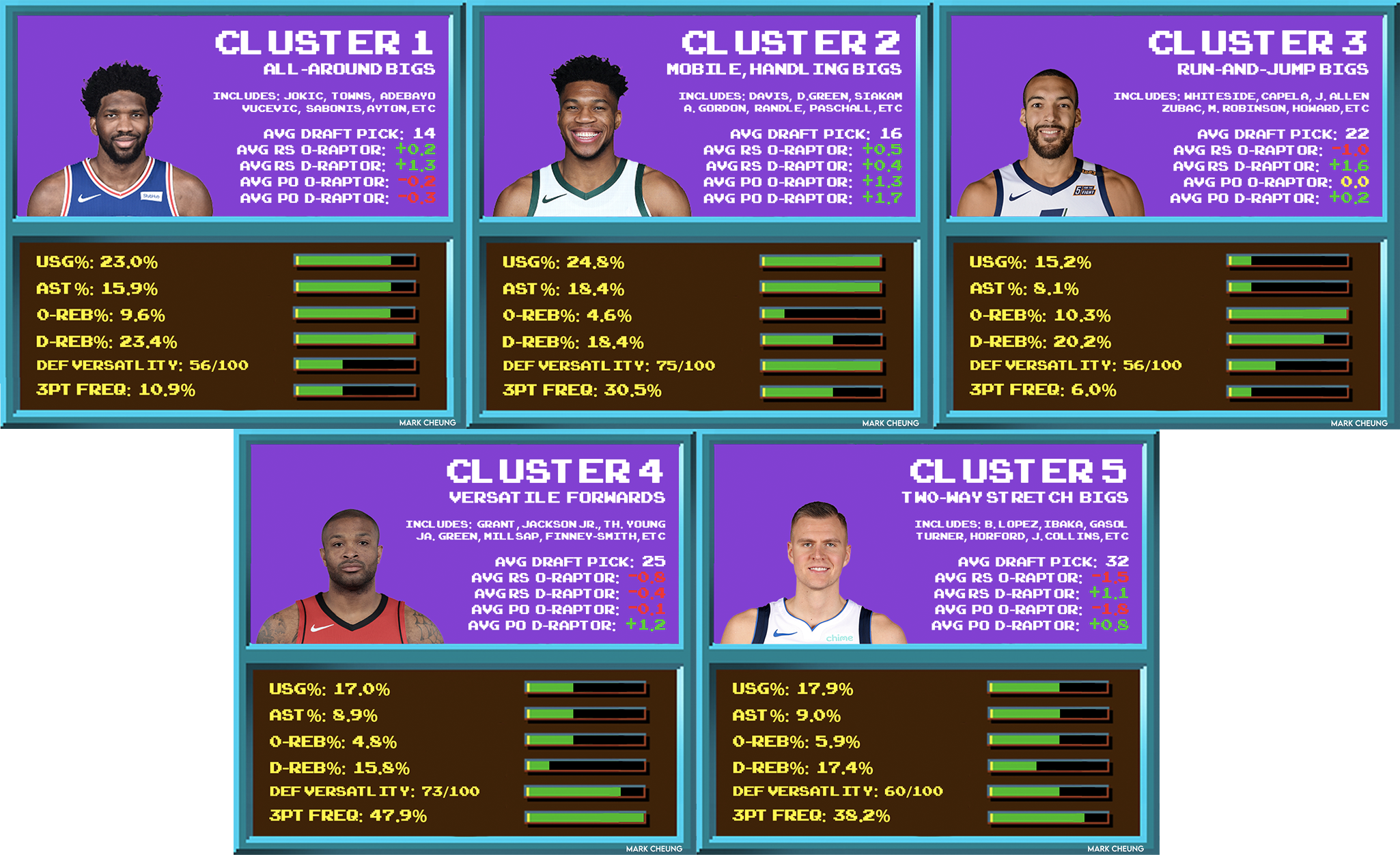

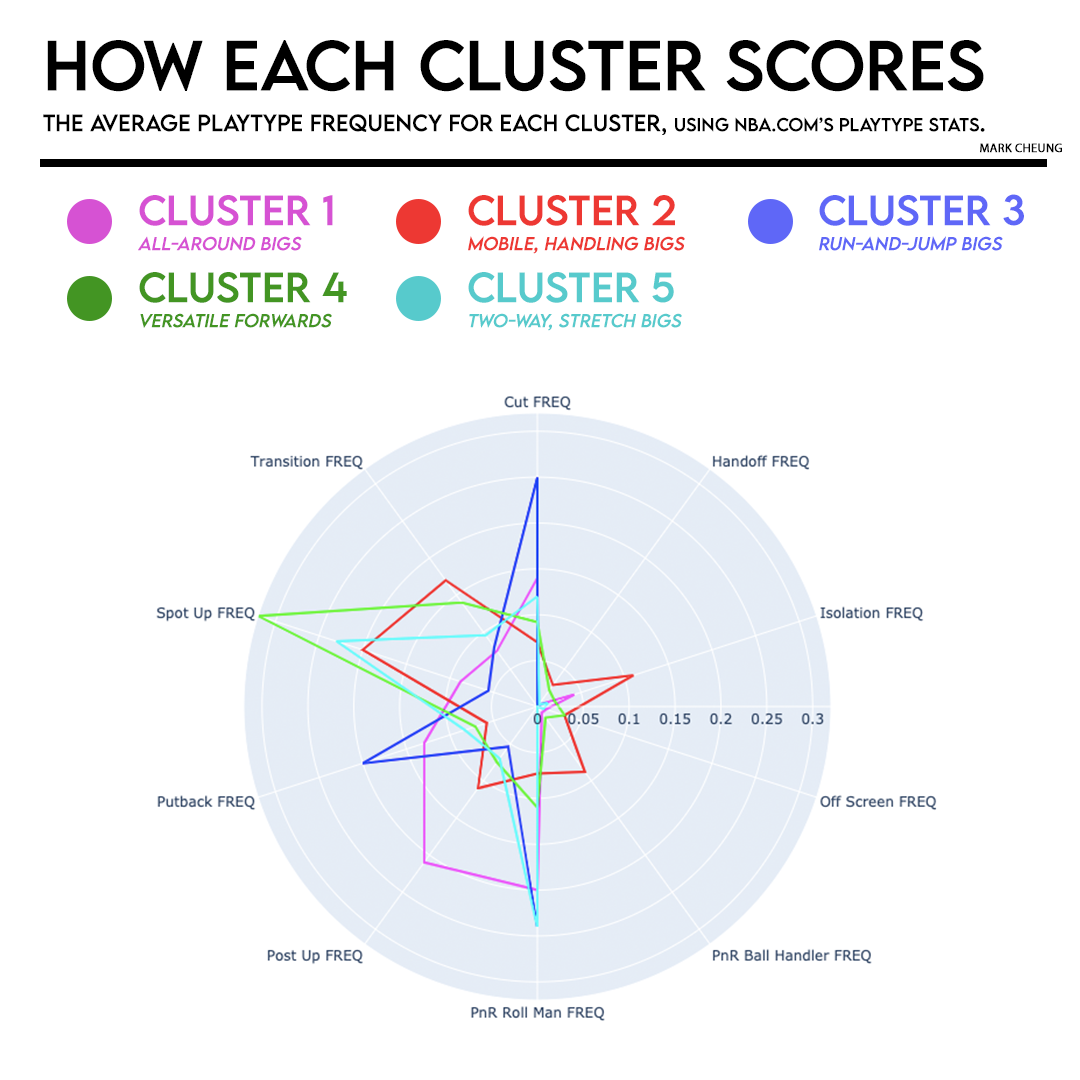

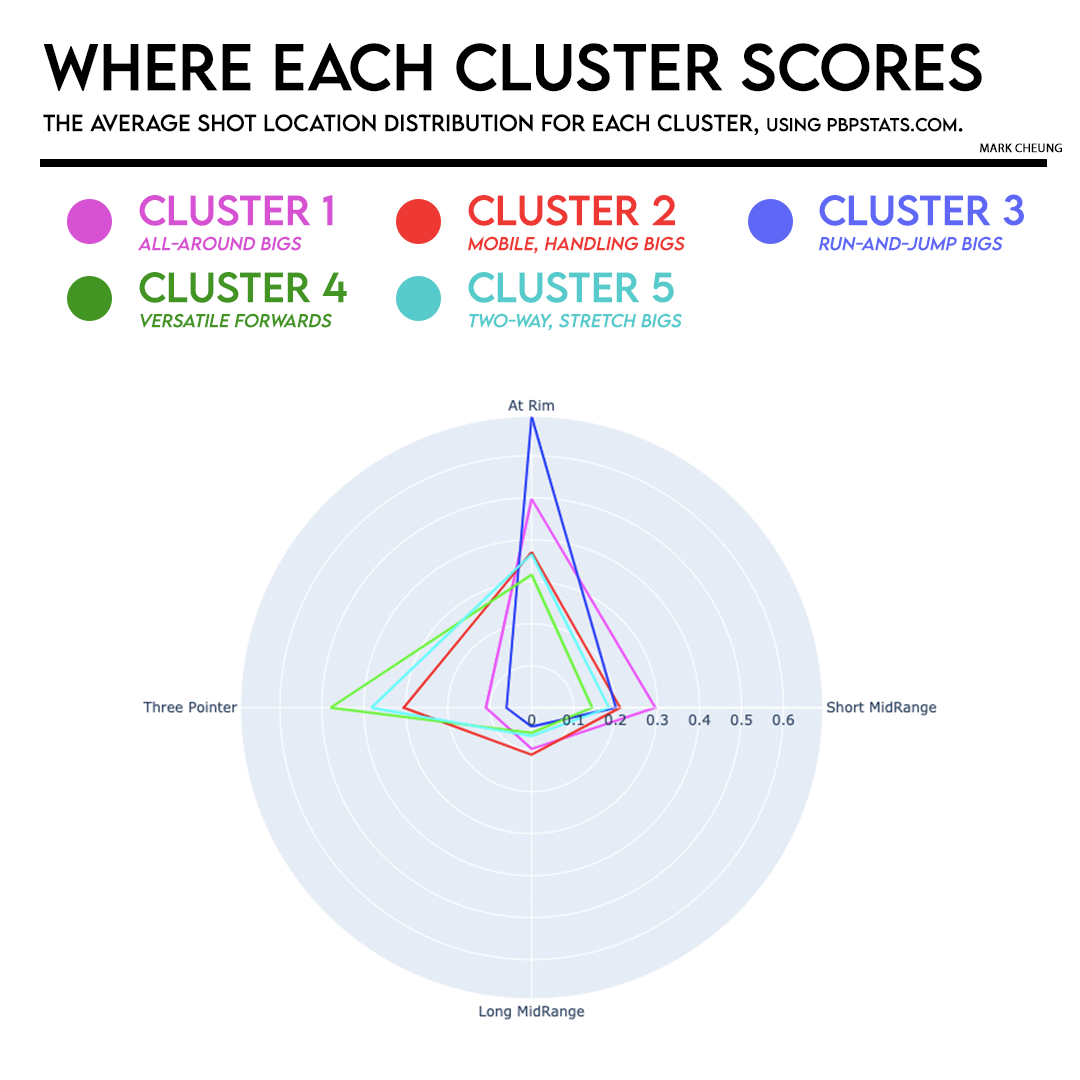

Now that we have an idea of how these players are clustered and what that that looks like spatially, here’s a brief overview of what each cluster looks like in the more commonly spoken basketball language (all stats are from 2019-20):

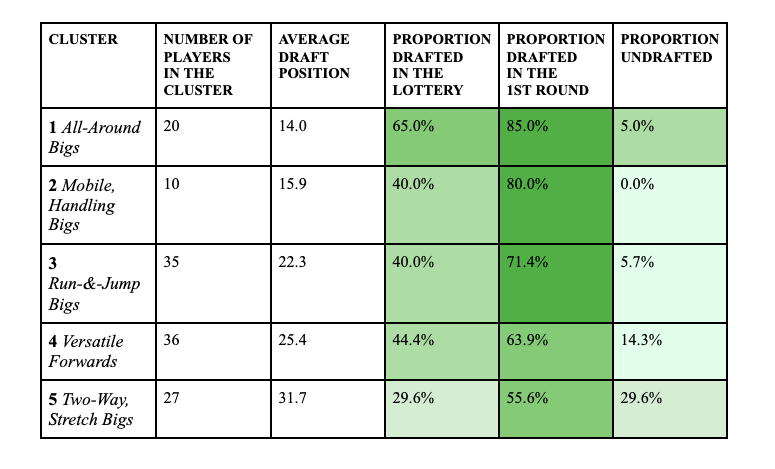

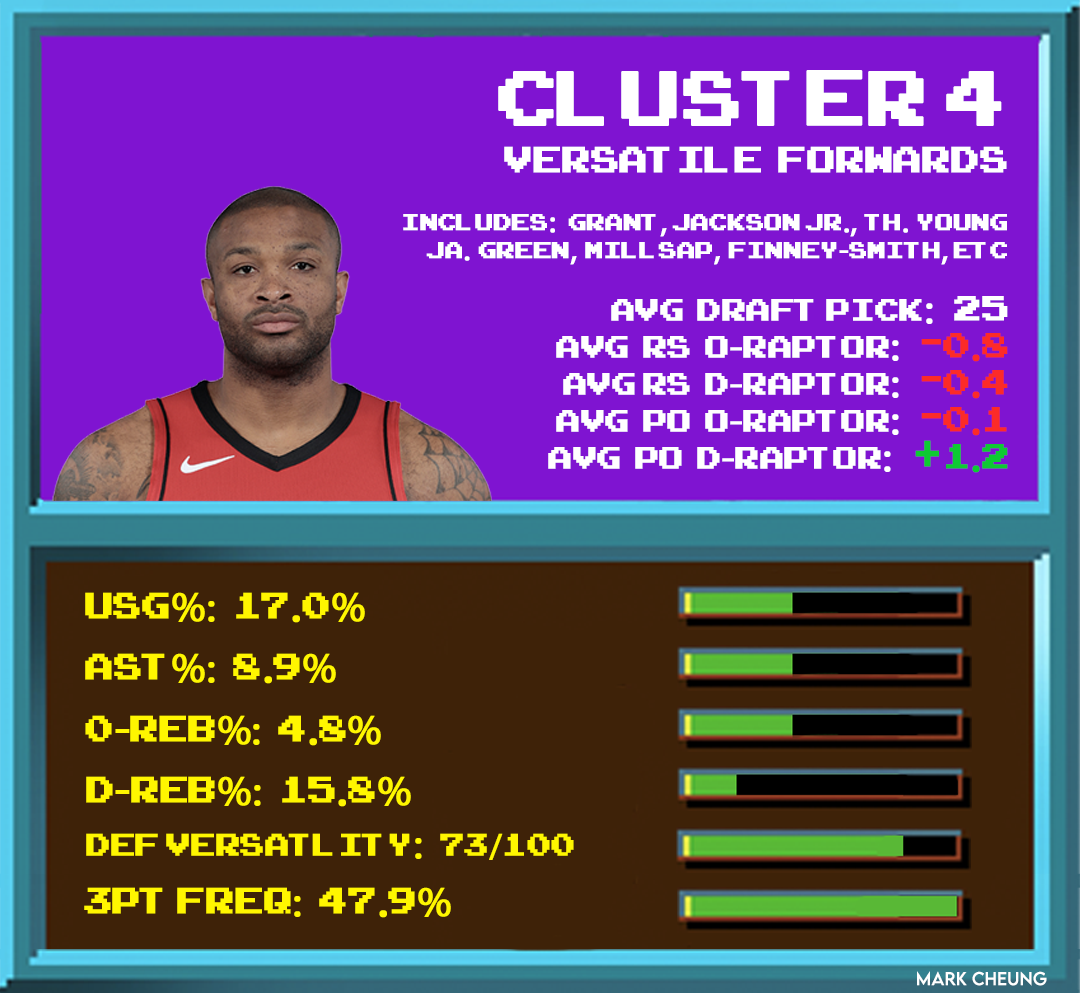

Feel free to zoom in. (Note: The green attribute rating bars are based on where each cluster ranks relative to the other 4 clusters (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th).)

In general, Clusters 1 and 2 hold most of the household names, meanwhile Clusters 3, 4, and 5 contain more specialists/role-players.

Diving a little deeper:

- Clusters 1 and 2 provide the most offensive impact (via RAPTOR) in the regular season.

- Clusters 1 and 3 provide the most defensive impact (via RAPTOR) in the regular season.

- Clusters 1 and 2 lead the pack in on-ball statistics, like usage rate and assist percentage.

- Clusters 4 and 5 are the highest frequency outside shooters out of the bunch.

- Clusters 2 and 4 are the most defensively versatile.

- Clusters 1 and 3 secure the highest % of available rebounds.

Here’s a comparison of each cluster's average methods of scoring - specifically, how and where they score:

The Analysis

Now that we’ve gotten all of our bigmen into their clusters, we can finally get into the meat of our analysis. In what order are these archetypes getting drafted in and what order should these archetypes be getting drafted in? Are front offices making the correct investments?

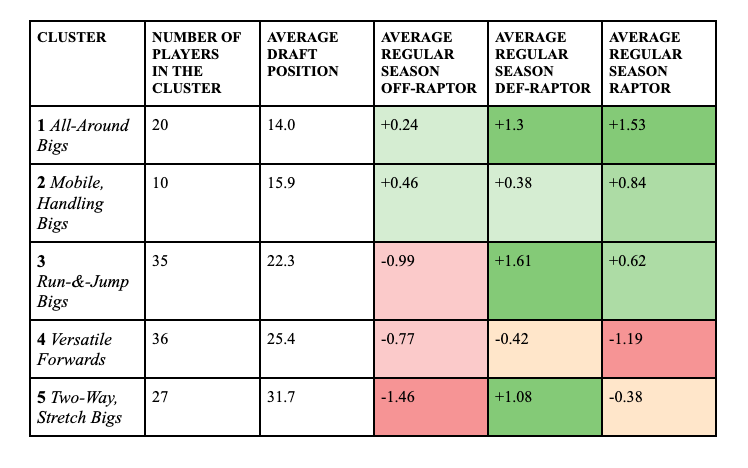

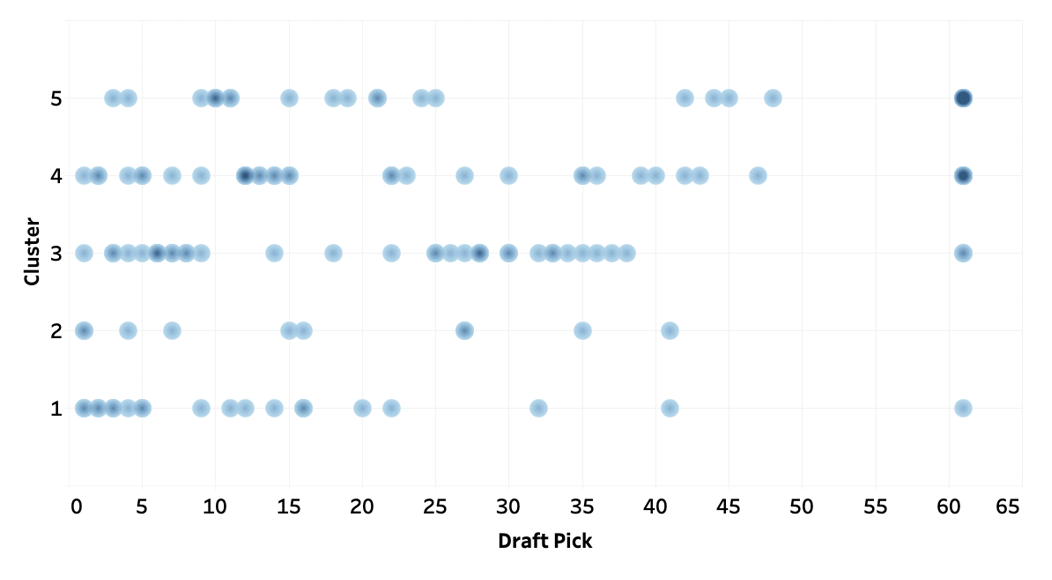

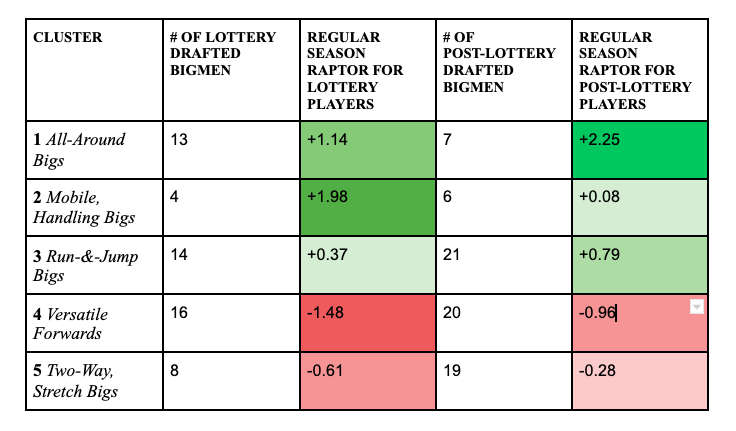

Below is a table of average draft position and average impact of each archetype.

When comparing average draft position to average RAPTOR, things look pretty reasonable. For the most part, there’s a positive association between average draft position of a cluster and average RAPTOR of a cluster, suggesting that the right archetypes are usually being drafted in the right places. Unsurprisingly, the star-studded All-Around Bigs, featuring Joel Embiid, Nikola Jokic, KAT, and Bam Adebayo, are the highest drafted archetype on average and they also lead the way in terms of impact with a blistering +1.53 average RAPTOR. Next in line are the Mobile Handling Bigs, home of Giannis, AD, Siakam and Draymond - which also makes plenty of sense.

But outside of those two elite groups, defining the value of the other three clusters is a little cloudier. Let’s take a closer look.

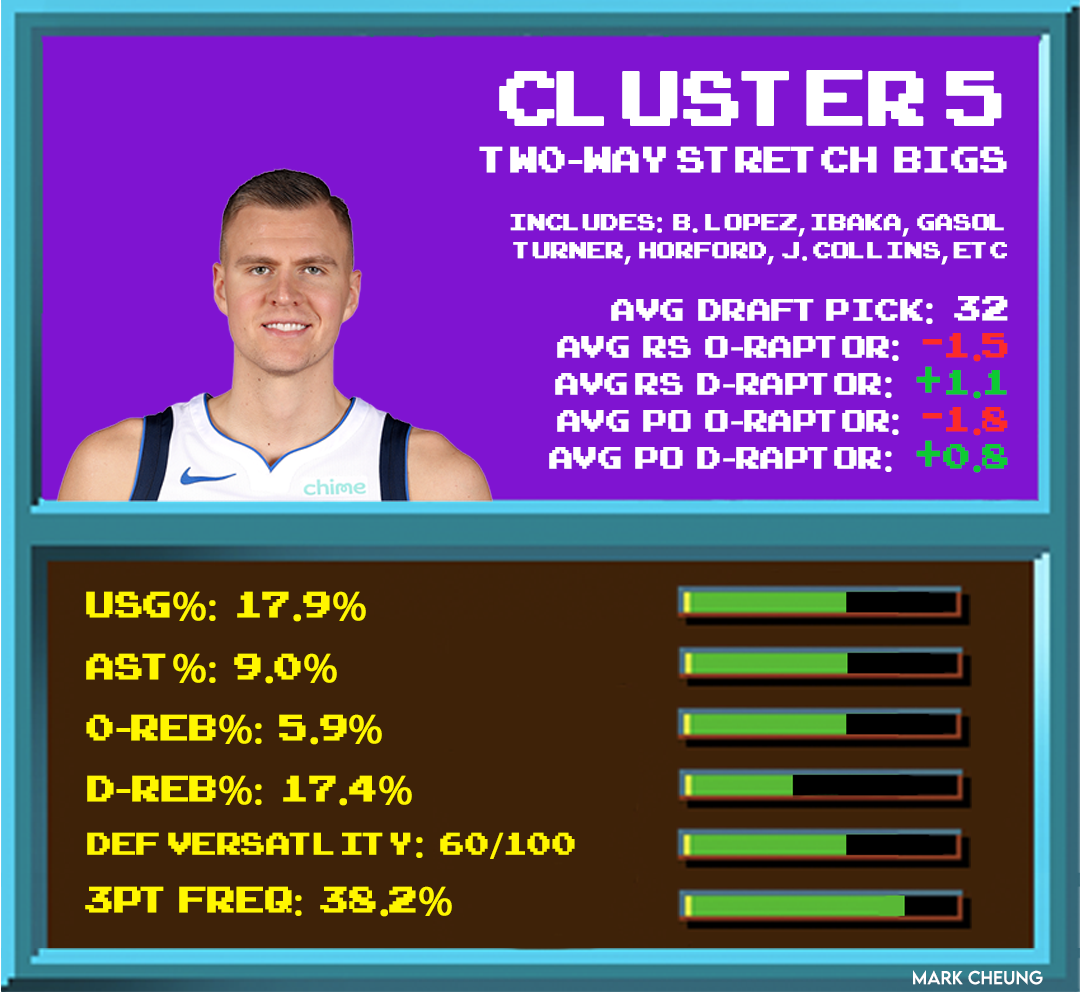

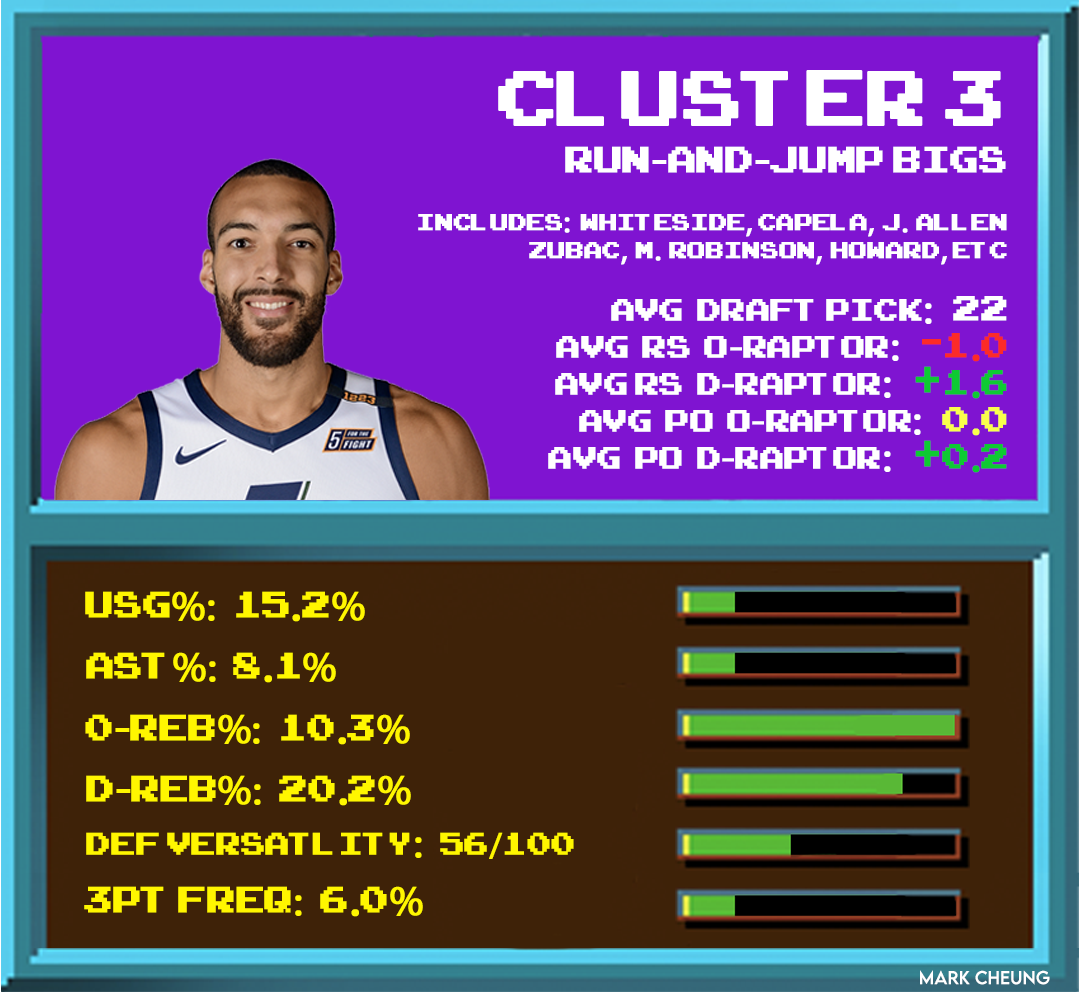

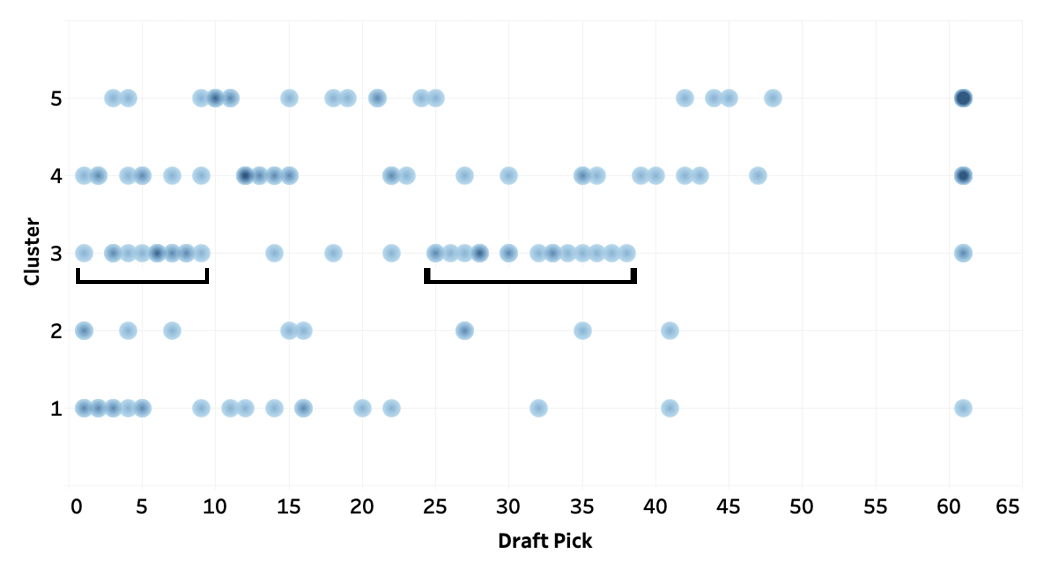

Cluster 5: Two-Way Stretch Bigs

Finding that Two-Way Stretch Bigs are at the caboose of average draft position is somewhat surprising considering that this “unicorn” skillset has been highly coveted both for its rarity and for its alignment with modern NBA playstyles. This plot, which shows where all the bigmen in our dataset were drafted (sorted by cluster and shaded by density), reveals that there is not a ton of high-end draft talent in this cluster.

Lottery picks are scarce - featuring the select dazzling few that carry the name of the archetype, such as Kristaps Porzingis and Brook Lopez. Meanwhile, the majority of the cluster is concentrated post-lottery, especially post-draft.

One theory on why so many back-of-the-draft bigmen inhabit this archetype could be because back-of-the-draft players tend to not be extremely skilled in one or more areas (or else they would’ve been drafted higher). That aligns with this archetype because a lot of its constituents make their money off being able to do two things (shooting and rim-protection) at competent levels, rather than excelling at one thing. To paint a picture, some of the bigs who were classified into this cluster were Dewayne Dedmon, Thon Maker, Robin Lopez, and Aron Baynes (reminder, this is from 2019-20). Maybe a better-suited name for this archetype would’ve been “1.5-Way Stretch Bigs”.

Thus, you could make an argument that the average impact of this archetype says something about the value of “dabblers” vs “specalists”. Not only are Two-Way Stretch Bigs’ overall RAPTOR impact not great, but the offense/defense breakdown is puzzling. An -1.46 offensive RAPTOR is not good. It’s easily the worst out of the 5 clusters, and it’s also antithetical to what we would expect from this archetype. The whole idea of a Two-Way Stretch Big is to provide more value on offense via floor spacing compared to an average big, without fully compromising defense. Because of that, you’d think that they would have a higher offensive impact and a slightly lower defensive impact relative to a cluster like Run-and-Jump Bigs. The defense checks out, but the offense oddly doesn’t.

I wonder if this has to do with how the league is trending towards shooting and spacing. In a way, the very same shooting movement that fueled this archetype's popularity has also been the meteor to its existence. For instance, the eradication of two-big lineups and the subsequent popularization of one-big lineups has partially erased the need of floor-spacing from the bigman position. It makes sense why you would need a stretch big if he’s playing alongside another paint-centric big. But when you have 4 perimeter players on the court, the floor is already going to be spaced - and at that point, it’s probably more advantageous to have a potent roll-man/paint threat or short-roll passer that can activate the surrounding perimeter players. Additionally, as floor-spacing continues to kill off the population of immobile bigs - by dragging them out of the paint in 5-out arrangements or by exposing their drop coverages in pick-and-pops - it’s also going to render one of the stretch big’s most valuable services (exposing immobile bigs) obsolete. If there are no more pests around, the exterminator has no more use.

As a general statement, because spacing has become such a ubiquitous and replaceable skill - stretch bigs are no longer a rare, hot-wanted commodity anymore. Their special skill is still valuable, but no longer special.

Despite this curiously low offensive RAPTOR, Two-Way Stretch Bigs still contribute respectable value, clocking in at an average of -0.38 RAPTOR. While their negative impact might be off-putting, it’s not that bad when you consider that

- Almost half of these players are being drafted past the first round.

- Almost one-third of them were undrafted,

- RAPTOR defines a replacement-level player as having -2.75 impact.

A roughly neutral-impact player isn’t exactly negative value if you only spent a 2nd round pick on them.

In large, these findings mildly suggest that: From a team standpoint, you don’t need to be drafting Two-Way Stretch Bigs that high since they’ve historically been available later in the draft, and because most don’t offer positive value relative to specialists unless they have significant peaks in both shooting and rim-protection.

In the context of the recent 2020 NBA draft, this could strengthen the argument that the Phoenix Suns taking Jalen Smith - who sported a 36.8% 3P% and 2.4 blocks per game at Maryland - with the 10th overall pick was a stretch. I don’t mind Jalen Smith as a prospect (and I’m by no means a draft expert), but I can understand the reasoning that he’s simply not standout enough in either shooting or defense to warrant a selection as high as 10. And if history suggests that this archetype could be found later in the draft, the Suns could’ve gotten more bang for their buck had they drafted a more valuable archetype with their lottery pick.

And if you consider James Wiseman as identifying most closely to a “Two-Way Stretch Big”, these findings cast some doubts on his median outcome. With the track record of this archetype, there’s a chance that he could go down as a disappointment relative to his draft selection unless he ascends into a much higher echelon as both a shooter and rim-protector. But perhaps his overlap into this next archetype could dilute those pressures.

Cluster 3: Run-and-Jump Bigs

According to average regular-season RAPTOR, Run-and-Jump Bigs appear to be one of the best value plays out of the five archetypes. They lead the pack in defensive impact and their overall impact is only a hair behind the much more highly revered Mobile-Handling Bigs archetype - all while having an average cost of ~6 picks lower than Mobile-Handling Bigs.

However, this all might be a little too good to be true - and we’ll soon explore how this archetype stacks up in different contexts. But, in the mean time, there’s an interesting pattern occurring within this cluster that’s worth looking into.

Revisiting the draft position plot, there appears to be two mini-clusters forming within Run-and-Jump Bigs (Cluster 3). There’s one bunch of R&J bigs getting drafted in the top-10 and another bunch getting drafted between 25-40, with few going in-between or after. At first thought, the most sensible reasoning for this would be that the R&J bigs being drafted in the lottery are simply higher caliber athletes/defenders compared to the “B-tier” R&J bigs falling to the 20s and 30s.

But, by splitting the numbers up, we actually find that these two groupings are impacting the game at nearly identical levels, despite the difference in draft position.

The average RAPTOR of the 14 lottery-level Run-and-Jump Bigs was +0.37 last season. Meanwhile, the average RAPTOR for the 21 Run-and-Jump Bigs drafted outside of the lottery was +0.79. With the small sample size that we are working with, this should be taken with a grain of salt. For example, that huge difference in RAPTOR between lottery/post-lottery All-Around Bigs is largely influenced by Nikola Jokic carrying huge weight in a sample size of 7. But, this issue is more mitigated with the larger sample sizes of Clusters 3.

One explanation could be that there’s a bias working in favor of post-lottery picks because lottery picks get more chances in the league, even if they are bad - meanwhile mid-to-late draft picks usually have to be good in order to stay in the league (and those that fall out of the league aren’t counted against their average impact here). However, a counteracting bias could be that lottery picks are expected to be better than post-lottery picks.

There may not be enough evidence to suggest that post-lottery R&J Bigs are better than their lottery counterparts - but even if you consider the difference in impact between the two as insignificant, that would still suggest that pursuing a R&J Big in the lottery is not a worthwhile investment. It would be more economical to trade down to the 20s/30s - where you can acquire a similar-caliber player AND reap an extra asset. There’s little need to draft Jaxson Hayes with a top-8 pick if you can get Jarrett Allen, Clint Capela, Robert Williams, Mitchell Robinson, Hassan Whiteside, or Nicolas Claxton (how did Claxton fall to 31 lol) in the 20s and 30s - obviously this is easier said than done, but it’s something to consider if those archetypes are available later in the draft.

In the context of the 2020 NBA Draft, I suppose this could apply to either of James Wiseman or Onyeka Okongwu depending on your level of pessimism. If you don’t buy Wiseman’s 11-30 sample on three-pointers and you don’t see the light on his paltry 0.77 PPP on post-ups - then there’s an argument to be made that the Warriors made a mistake by spending their number 2 overall pick on an archetype that produces similar value in the mid-to-late first round. And if you don’t buy that Onyeka’s post-game will translate versus stronger/taller defenders nor that his defensive versatility will translate versus quicker/craftier perimeter players - then you can make a similar argument about the Hawks selecting him at 6. Although, looking on the brighter side, I think this next archetype shines a ton of optimism on what Onyeka could bring to a team if his defensive versatility pans out.

Cluster 4: Versatile Forwards

So, are Versatile Forwards just completely garbage? The 36 Versatile Forwards in the NBA averaged an abysmal -1.19 RAPTOR last regular season, despite being picked in the first round on average - over 6 spots above Two-way Stretch Bigs and just a few spots below Run-and-Jump Bigs. This comes at a complete contrast to the way the league has seemingly been trending. Some of the best teams in the NBA have been very competitive on a platform of versatility, namely the Finals-runner-up Miami Heat. Isn’t this supposed to be the archetype of the future?

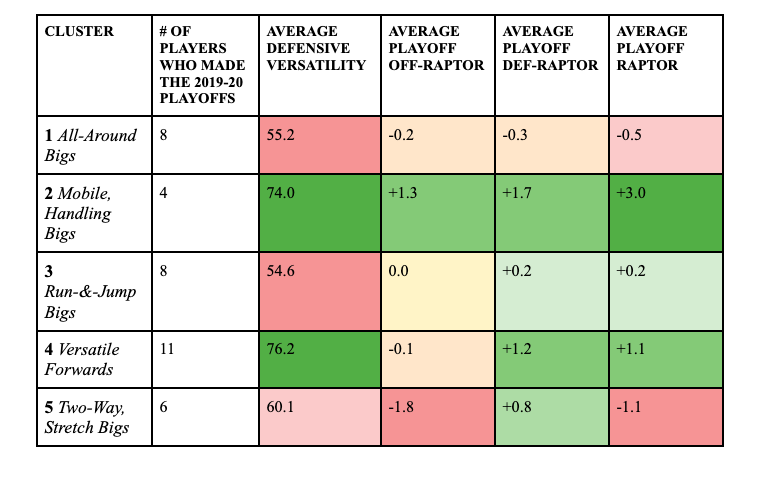

The answer is yes, and there’s more to the story. Even though Versatile Forwards have had uninspiring impact in the regular season, we see a huge positive shift in impact during the playoffs.

While these numbers are also plagued by small sample sizes in terms of both players and playing time - there’s still a credible storyline being painted (that’s also backed up by the eye-test). The two most defensively versatile archetypes (Clusters 2 and 4), according to Krishna Narsu’s defensive versatility rating, had the most positive impact in Defensive RAPTOR during the 2019-20 playoffs - with Versatile Forwards' defensive RAPTOR swinging 1.6 points in the positive direction.

I don’t think this is just a coincidence either. We saw Frank Vogel opt for the more versatile Markieff Morris on multiple occasions instead of Dwight Howard or Javale McGee. Erik Spoelstra stopped playing Meyers Leonard, their starting center in the regular season, altogether in the playoffs. Brad Stevens played Grant Williams, a 6’6” swiss-army-knife big, almost 70 more minutes than Enes Kanter in the playoffs.

Not only did defensively versatile bigs appreciate on defense in the playoffs, but defensively inflexible bigs depreciated on defense in the playoffs. Run-&-Jump bigs, who had the highest defensive impact in the regular season (+1.6), were almost a neutral on that end in the playoffs. And All-Around bigs, who had the second highest defensive impact in the regular season (+1.3), dropped below 0 during the postseason.

And this makes sense when you think about the matchup-intensive environment of the playoffs. In a 7-game series versus a single opponent, coaching staffs are able to devote a lot more attention towards diagnosing and strategizing against their foes’ achilles heels. Players with more pronounced weaknesses will get exposed - think of Jamal Murray abusing the Clippers and the Jazz’s drop-coverage in the pick-and-roll. While Versatile Forwards may lack the peaks in major areas that other archetypes possess, they have fewer weaknesses that can be exploited - and perhaps that’s the biggest strength of them all. So even though Versatile Forwards’ negative regular season RAPTOR might suggest that they are being drafted too high, the opposite might be true - rather, they aren’t being drafted high enough.

As a result, Deni Avdija and Patrick Williams could end up having two of the highest median outcomes in the 2020 NBA Draft just because of archetype alone. And towards the end of the draft, multi-positional defenders Tyler Bey (#36 to Dallas) and Paul Reed (#58 to Philadelphia) could end producing above their draft position as second-round picks - especially since they both were taken by playoff teams.

Conclusions

At the end of the day, this analytical analysis can only take you so far. 128 bigmen cannot be perfectly partitioned into just 5 groups and there’s always going to be high-end talent at the top of each archetype that transcend any overarching trends. But, at the very least, there’s still some guiding (although, perhaps not novel) principles to be taken away that could lead to a better evaluation of the current NBA landscape.

- For most bigmen archetypes, you are usually be able to find similar-caliber players later in the draft than you’d might think (this is especially the case for Run-and-Jump Bigs, Versatile Forwards, and Two-Way Stretch Bigs). So drafting a more valuable perimeter-oriented position with a high pick or trading down to take a big are often more efficient options.

- Playoff teams should prioritize Versatile Forwards more in the draft. And there’s historically been plenty available in the range that playoff teams draft (post-lottery).

- All-Around Bigs and Run-and-Jump Bigs often provide great value in the regular season, which can boost rebuilding teams trying to elevate out of the cellar, or mid-tier/fringe playoff teams fighting for seeding. But these two archetypes are less effective in lifting teams over the next hump of becoming a legit contender because of their drop-off in impact during the postseason